News from the Brazilian Social Security Service Provision Front

To wrap-up this trilogy about Brazilian Social Security implementation, I will now go through the three most relevant endeavours being carried by the country’s national social security agency (INSS), in its efforts to deal with the challenges described in my previous post.

All of them are strongly reliant on information systems, which are actually delivered by Dataprev, the public company which develops INSS’s for INSS. Yet, they involved several regulation changes, services’ redesign, and procedure adjustments. There were long quests throughout the internal bureaucracy mazes, from conception to implementation and evaluation.

Digital Transformation

Until 2018, most of INSS services were provided through in-person encounters in service offices. Its Internet website and call centres could only provide general information and some limited details on benefit claims and payments – at most, they could book appointments in the offices. Further, virtually every single process in the organization was paper-based.

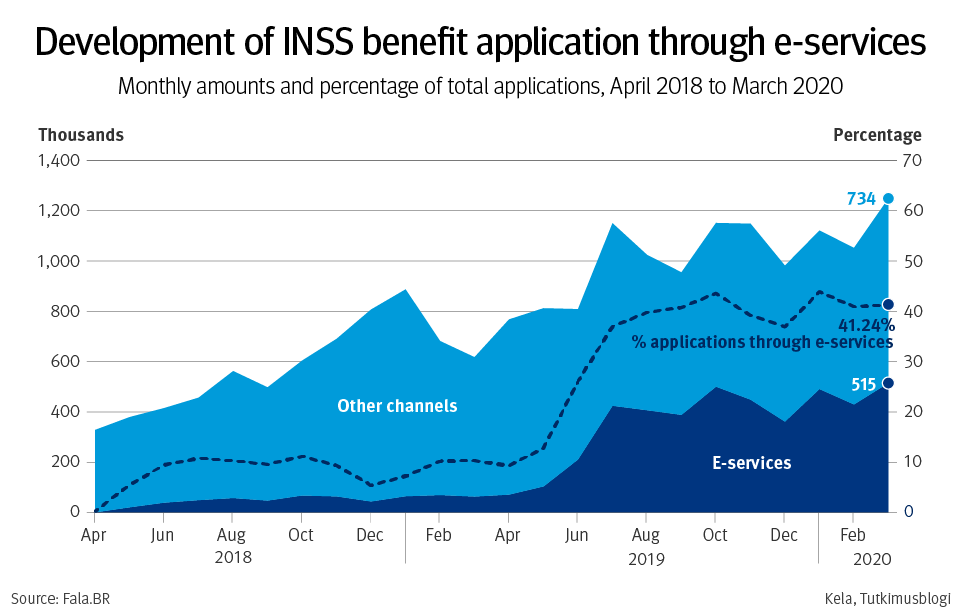

However, since mid-2014, efforts towards the agency’s digital transformation grew exponentially. At that time, there was a sequence of new service delivery model projects’ proofs-of-concept (PoCs), supported by new regulations and software development standards set by Dataprev. These were the first steps to enable the INSS digital transformation, which went full steam in 2019. Three main software projects supported it: 1) GET, Portuguese acronym for ‘task manager’, a single web platform for process stages control and automatic task assignment according to officials’ competences; 2) SAG, ‘booking system’, which receives requests (‘bookings’) and controls the agency’s workforce’s task capacity; and 3) Meu INSS, e-services front-end and app. Figure 1 shows the evolution of e-services use between April 2018 and March 2020:

Figure 1. April 2018 to March 2020 development of INSS benefit application through e-services – monthly amounts and percentage of total applications. Source: Fala.BR, claim n. 03006.015117/2020-88.

So, in March 2020, the last month before the coronavirus pandemic onset in Brazil, 515 thousand applications were filed through e-services, 41.24% of the total, after two years of progressive implementation. INSS’s digital transformation also supported the more recent 2018 home office pilot project, allowing caseworkers to work from home – which was fully implemented during the first months of the coronavirus crisis. Finally, the program provided the platforms powering the next two initiatives’ development as well.

Collaborative Service Provision

Since at least 1991, the national social security law already enabled INSS to provide its services through partner organizations. However, in late 2014, the first PoC of the GET platform showed how partnerships could be powered by it. Afterwards, in 2016, a massive program of partnerships with fishers’ associations and unions was undertaken, to cope with the new demand for the processing of benefits due to closed fishery season, formerly done by contracted-out agencies. The partners’ job was then to orient their associated fishermen, receive their applications, and send them to INSS for analysis.

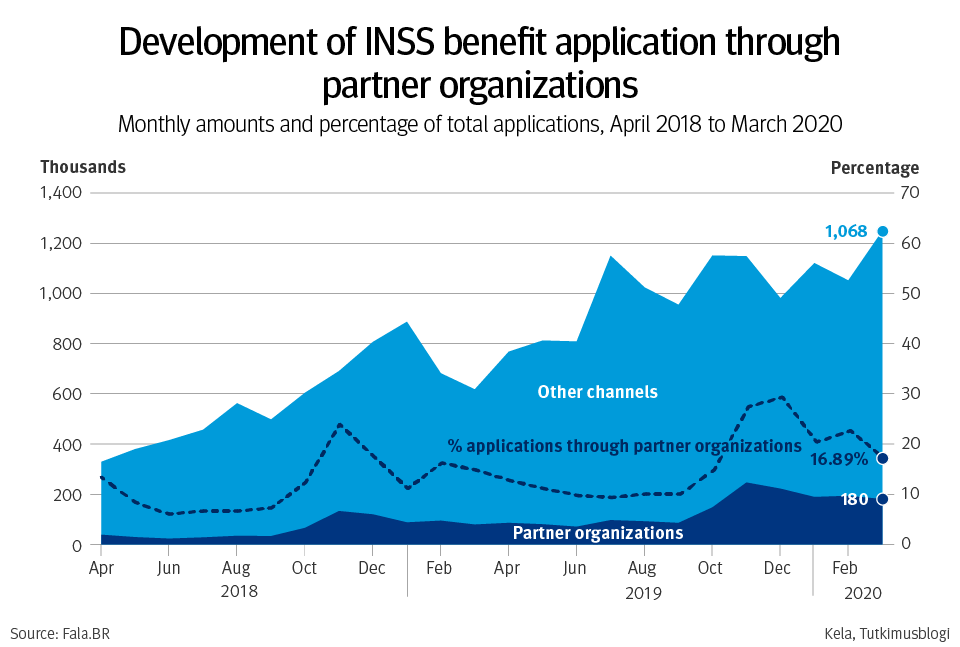

From late 2017 on, with the formal launching of the INSS digital transformation program, partnerships with municipalities and third sector organizations begun spreading all over the country. Powered by the newly delivered GET platform, partners could now receive every kind of application, monitor its status, and inform residents or associates about their cases. Figure 2 shows a growing trend of these applications, reaching more than 180,000 in March/2020, or 17% of total applications. The two highest hills in the percentage line, around the last months of 2018 and 2019, refer to the main fishery closed seasons, when most Brazilian fishermen are entitled to benefits. For this specific policy, service provision through partnerships became the rule, reaching 90% of all applications in December 2019 (Fala.BR, claim n. 03006.015117/2020-88).

Figure 2. April 2018 to March 2020 development of INSS benefit application through partner organizations – monthly amounts and percentage of total applications. Source: Fala.BR, claim n. 03006.015117/2020-88.

Besides expectable efficiency gains, the most relevant outcome of the collaborative service delivery platform is that the partnerships with local organizations enabled social security services to reach communities otherwise excluded from the regular delivery system. Further, the digital platform implies reduced transaction costs for partners, which are offset by the advantages of closer contact and engagement opportunities with their public. So, INSS does not provide financial compensation, and partner organizations are prohibited to charge for the services: offering free alternatives to the private service brokers discussed in my last post, the despachantes.

Benefit Granting Automation

Bearing the promise of delivering both more standardized decisions, less dependent on caseworkers’ discretion, and lower demand for specialized personnel, the quest for caseworking automation has been pursued since 2002, with the INSS ‘New Management Model’ program. As provided in that program, first, the different existing benefit granting and payment systems would be unified. Afterwards, the new system would be able to apply the complex business rules on available citizen administrative data, granting benefits with no need for caseworkers’ analyses.

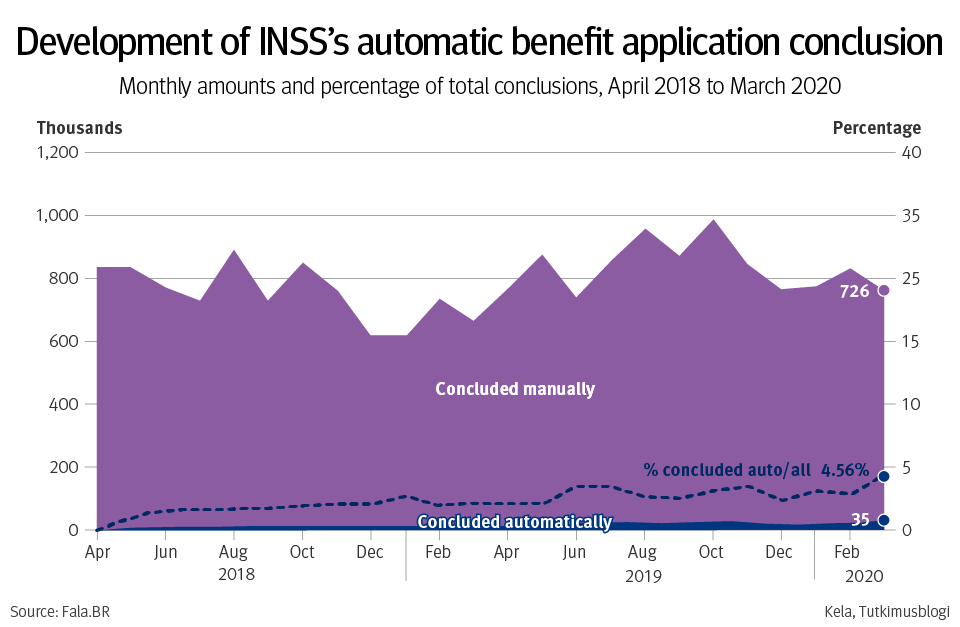

However, the unifying project is still in development today, and far from conclusion. Among other issues it faced, the most critical was the frequent shifts in benefit-granting rules, which asked for frequent project changes, and consequently delivery delays. So, in 2017, a joint team of service delivery and benefits department decided to launch a parallel experiment, in which the oldest benefit-granting system, Prisma, would be the one granting benefits automatically, through a component connecting it to the GET platform. A new system component, ‘PriGET’ (Prisma + GET), would batch scan the existing open applications and process any which could be granted automatically. With less than one year of development, PoC, piloting, and evaluation, PriGET was effectively launched in April 2018, and a share of benefits started to be granted automatically.

Figure 3. April 2018 to March 2020 development of INSS’s automatic benefit application conclusion – monthly amounts and percentage of total conclusions. Source: Fala.BR, claim n. 03006.015467/2020-44.

As Figure 3 shows, automatic granting grew steadily during the very first months after the project’s launch. Following a relatively stable trend, in March 2020, last month before the coronavirus crisis, 34,674, or 5% of cases were decided without any human intervention.

Conclusion

The described initiatives are managing to improve the INSS’s overall service delivery performance, though they do not fully address the root cause of its problems: the overly complex social security rules. The still shy ratio of automatic decisions (Figure 3) is a clue: rule intricacy implies dependence on caseworkers’ interpretations, setting the ceiling for full automatization. From the citizens’ standpoint, this complexity causes opacity and feelings of disappointment. Their expectations are bound to be frustrated, and their trust in the system compromised – regardless of super-smart service provision systems. This scenario keeps despachantes’ leverage: the for-profit public services’ brokers, regarded by clients as ‘experts’ in facing the State’s machinery, are still a ‘safer bet’ amidst the complex and deceiving maze of social security rules.

Luiz Alonso de Andrade

MPP, previously intern at Kelan tutkimus

luiz.alonsodeandrade@tuni.fi

More information

The Atlantic: A Day in the Life of Brazil’s Insane Bureaucracy

Previous blog posts about the Brazilian social security system

Four Challenges of the Brazilian National Social Security System’s Implementation

The Unlikely Brazilian Social Policy Response to Coronavirus – Basic Income Emergency Aid